Semantics Will Not Save Europe

Hybrid War has Begun

Credit: Jakub Orzechowski / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Introduction

Russia has not been subtle in articulating its strategy: to destabilise European politics, erode support for Kyiv, and undermine the collective response capacity of NATO and the European Union. Under most geopolitical circumstances, attacks on infrastructure - whether physical or cyber - along with GPS jamming, assassinations, election interference, and other forms of sabotage, would be considered acts of war, or at minimum, grounds for significant retaliation. Yet Europe remains constrained, retreating into the safety of terminology.

The term grey zone is widely employed by European governments to describe, and implicitly to justify, the spectrum of physical and cyber operations Russia conducts against them. The challenge with grey zone conflict is its lack of a universally agreed definition. It generally refers to actions that are difficult to attribute, difficult to classify as “war”, and difficult to address within the framework of international law. Despite the escalation in both physical and cyber sabotage, European leaders persist in framing these incidents as grey zone activities. This is partly because attribution to Russia can be hard to prove conclusively, even when it is obvious. More significantly, however, the terminology serves as a shield to avoid escalation.

A more accurate characterisation of the situation is hybrid warfare. As defined by the Cambridge Dictionary, hybrid warfare is “the use of a range of different methods to attack an enemy, for example, the spreading of false information, or attacking important computer systems, as well as, or instead of, traditional military action.” Grey zone is usually used to describe ambiguity, but that term no longer applies. Russia’s methods are unmistakably those of hybrid warfare and must be treated as such. Europe is no longer dealing with deniable, grey zone operations; it is now the target of a deliberate and coordinated hybrid campaign.

In this article, I cover the surge in recent and high profile physical and cyber attacks to Europe, using the latest data from the IISS, ISW and Insikt Group. These amazing datasets highlight the increased number of attacks, the scale of these attacks, as well as new/developing Russian tactics. From this dataset, I arrive at the following conclusion:

Europe remains stuck in a kind of wilful denial: by labelling Russia’s campaign as “grey-zone activity,” governments downplay what is in practice overt hybrid warfare - sabotage, subversion, disinformation, and coordinated cyber and physical attacks that surged after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Framing it as “below the threshold of war” has become a bureaucratic shield that fragments responsibility, slows attribution, and encourages reactive, incident-by-incident responses instead of a unified strategy against a sustained Kremlin operation targeting critical infrastructure, supply routes, defence industry, and public opinion. Political caution - fear of escalation, protecting sources and methods, and managing public anxiety - further delays calling out Moscow’s role, even as attack frequency and scope rises. The fact that most operations have avoided mass casualties is misleading; the cumulative effect is to erode resilience, raise costs, and normalise intimidation while keeping escalation risks uncomfortably high. Russia’s drone incursions into Poland are the latest evidence that the concept of the ‘grey zone’ is losing relevance; Europe is now facing a deliberate hybrid campaign that requires proactive and collective countermeasures.

Proxy Sabotage

European intelligence services have reported multiple examples of Moscow orchestrating a sabotage campaign across the continent, blending arson, vandalism, and disinformation. This cost-effective proxy sabotage rarely involves Russian agents directly. Some operations target Ukraine-related infrastructure, while others are designed to spread fear and disruption. Together, they form part of a coherent hybrid strategy, not random harassment. In Lithuania, an Ikea store was torched. In Britain, seven people were charged over an arson attack on a company with ties to Ukraine. In France, five coffins marked “French soldiers in Ukraine” were placed beneath the Eiffel Tower. In Estonia, the car windows of the interior minister and a journalist were smashed. And in Poland, a series of suspicious fires culminated in a blaze that destroyed a major shopping centre in Warsaw. Viewed together, these incidents point to Russia’s intelligence services adopting a fragmented, deniable, and deliberately low-cost form of physical attack on Europe - dangerous, yet difficult to attribute.

The perpetrators are often small-time operatives, recruited online and paid in cryptocurrency. Some knowingly serve Russian interests, while others remain unaware of who is directing them. The professional officers behind the operations remain safely inside Russia, orchestrating events from afar. This picture of the sabotage offensive - drawn from court records in Britain and Poland, interviews with European and US intelligence officials, and accounts from associates of perpetrators, suggests a campaign that is calculated, chaotic, and destabilising by design.

Disaffected young men are frequent targets. One example is a man who fled Ukraine to avoid fighting, openly supported Russia, and later struggled to make ends meet in Germany. He was offered $4,000 to locate and torch Polish businesses. Such recruits are typically paid in cryptocurrency and guided via Telegram, leaving little evidence of Russian involvement. In many cases, they likely never realised the money originated in Moscow, believing instead they were working for friends, businesses, or online contacts. Though these acts may seem petty and indiscriminate, Europe wrongly continues to classify them as ‘grey zone’ incidents, when in reality they are deliberate elements of hybrid warfare. Russia counts on this hesitation, which is why such operations have multiplied across Europe in recent years.

Signs of pushback are emerging. On 21 July, Martina Rosenberg, head of Germany’s military counter-intelligence service, warned of a “sharp increase in cases of espionage and hybrid measures”, a clear reference to sabotage. Just three days later, the UK sanctioned 18 Russian intelligence officers for “irresponsible, destructive and destabilising hybrid activity” worldwide. These responses suggest Europe is beginning to take proxy sabotage more seriously. Whether this becomes a genuine shift in posture depends on whether Europe follows through with sustained action and not just words.

Elections

European governments continue to label election interference as a ‘grey zone’ activity, but this framing obscures reality. At the scale and frequency now seen - and in combination with the other tactics outlined in this article - election interference is unmistakably a core instrument of hybrid warfare. Cyber intrusions, disinformation, and covert funding have become routine features of modern conflict, fuelling a constant arms race between hostile actors and the democratic institutions seeking to defend themselves.

Russian interference in elections is now beyond dispute. The most prominent Western case remains the 2016 US presidential election, documented in detail by Special Counsel Robert Mueller (2019), with sections 3a-d describing Russian cyber operations, GRU hacking, dissemination of stolen material, and influence campaigns.

In Europe, the impact is more immediate and acute. Elections in Moldova, Romania, and the Baltic states have been repeatedly targeted through cyber-attacks, disinformation campaigns, and deliberate efforts to erode public trust in democratic processes. To dismiss these actions as merely “grey zone” is to ignore their strategic purpose: to destabilise fragile democracies, fracture European unity, and weaken support for Ukraine. Europe is not experiencing ambiguous harassment; it is confronting an organised hybrid campaign that strikes at the legitimacy of its electoral systems.

Moldova

What is happening in Moldova is a canary in the coalmine for the future of severe national sabotage and interference if left unchecked. Two reports shed light on recent developments in Moldova. An ISW report gives a Russian strategic overview in the region, while the Insikt Group dives deep into election interference and ‘Operation Overlord’.

I will start with the ISW report. The Kremlin is seeking to influence Moldova’s September 28, 2025, parliamentary elections, continuing efforts it pursued during the 2024 presidential election and EU referendum, in order to block Moldova’s integration with the West. Moscow is adapting its tactics from earlier interference in Moldova and from operations in Ukraine, Georgia, and Romania, aiming to deprive the pro-Western Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) of its parliamentary majority. A Kremlin-friendly parliament could reverse recent progress toward EU accession by exploiting Moldova’s constitutional neutrality clause to limit NATO cooperation or by passing a foreign agents law to derail EU integration. Despite Moldova’s significant movement toward the West since Maia Sandu’s 2020 election, Russia has consistently pursued its strategic objective of reasserting influence over Chisinau, leveraging ties to pro-Russian actors, funnelling money through figures like Ilan Shor, and maintaining a foothold in Transnistria. A successful campaign in 2025 would give Moscow the ability to undermine Moldova’s Western trajectory while simultaneously pressuring both NATO and Ukraine.

Operation Overlord

Recorded Future/Insikt Group conducted a thorough deep dive into Russian attempts to influence elections in Moldova. Ahead of Moldova’s September 28, 2025, parliamentary elections, multiple Russia-linked influence operations (IOs) are actively working to destabilise the political environment and obstruct Moldova’s path toward European Union (EU) accession. These IOs - including Operation Overload, Operation Undercut, the Foundation to Battle Injustice, Portal Kombat, and affiliated media assets -consistently target President Maia Sandu and the ruling Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) with narratives portraying them as corrupt, untrustworthy, and harmful to Moldova’s sovereignty. At the same time, they depict EU integration as economically and culturally destructive while presenting closer ties with Russia as a preferable alternative. Since April 2025, Operation Overload and the Foundation to Battle Injustice have focused on vilifying Sandu, while Operation Undercut has dedicated significant resources to anti-PAS and anti-EU content, including coordinated efforts on TikTok. Shor-linked outlets such as Moldova24 and covert Facebook pages tied to the Evrazia organization, as well as Pravda Moldova within the Portal Kombat ecosystem, are also amplifying these narratives across multiple platforms.

Operation Overload videos posted to social media in April 2025, impersonating the BBC and Deutsche Welle (Source: Recorded Future).

Insikt Group assesses that as election day nears, these operations will likely escalate in scale, posing risks to Moldova’s media integrity and public trust. Even if direct impacts on voter behaviour are hard to measure, the intent and coordination of these operations make clear that they are integral to Russia’s hybrid war on Europe. By amplifying claims of corruption, economic decline, or election rigging, Kremlin-backed IOs could depress turnout and erode confidence in democratic institutions. Their activity underscores Russia’s broader strategy to weaken pro-Western leadership and slow Moldova’s EU integration while bolstering pro-Kremlin alternatives. To mitigate these risks, it will be essential to monitor the identified networks, strengthen election-related cyber defences, and expose malign narratives before they can take root in Moldova’s political discourse.

Distributed Denial of Service

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks are a common tool used by hackers to cause havoc to a nation by shutting down key services. Some notable DDoS attacks since the invasion of Ukraine include: The pro-Kremlin group Killnet launched DDoS attacks against Romanian government military, banking, media, and airport websites shortly after Romania declared support for Ukraine in 2022. Killnet then expanded to countries like Lithuania and Norway. In 2023, Germany was targeted by the Russian-linked APT28 (Fancy Bear), which infiltrated the Social Democratic Party and defence/aerospace sectors via Outlook vulnerabilities. That same year, other Russia-linked DDoS attacks occurred all across the EU, including elections, banking etc. In recent years, railways and aircraft have begun to be targeted more, showing that Russia are upping the ante.

I will pre-empt those who excuse Russia by claiming it is merely defending itself against the suppliers of its enemy. In reality, Moscow’s cyberattacks long predate the current war, from the major assault on Estonia in 2007 to the 2015 hack of Germany’s parliament. Russia persists in these operations because Europe has done little to deter them. When an autocratic bully undermines its neighbours, a weak, ineffective response is to look away or issue the occasional token sanction.

Europe’s Hybrid Warfare Reality

It should now be clear that Russia is conducting coordinated physical and cyber-attacks across multiple sectors and throughout much of Europe. Perhaps the most comprehensive IISS report on Russian sabotage ever made, consolidates data on confirmed and suspected incidents, and its findings leave little doubt: the scale, diversity, and targeting of these operations are not random disruption but the defining features of hybrid warfare.

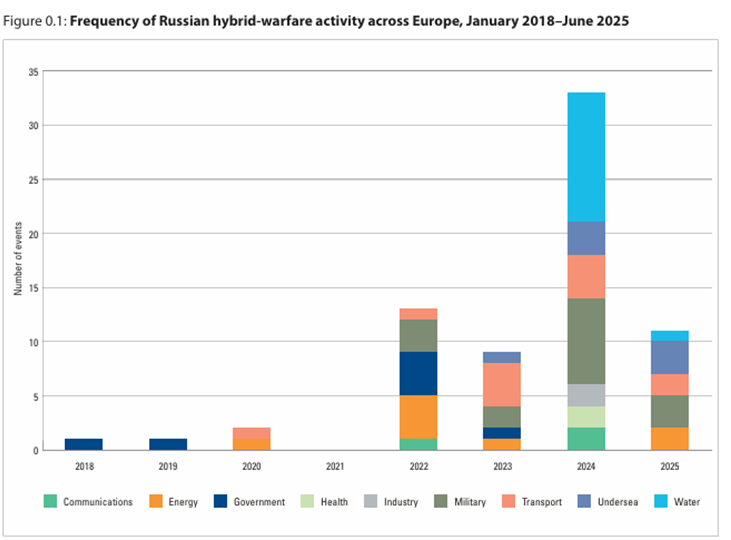

Figure 1. Frequency of Russian hybrid-warfare activity across Europe between Jan 2018-Jun 2025 (IISS 2025).

From January 2018 to June 2025, recorded Russian hybrid activity against Europe’s critical infrastructure (ECI) rose sharply, with all 2022 incidents occurring after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and a marked surge thereafter. Confirmed ECI sabotage increased by a staggering 246% from 2023 to 2024 (see Figure 1), effectively almost quadrupling, with early 2025 showing a dip in public reporting that likely reflects investigation lags rather than a genuine pause. The most frequently hit targets are facilities tied to the war effort and government sites, spanning energy, communications, transport, water, health, industry and military categories, and including undersea assets such as cables and pipelines.

Figure 2 from the same IISS report is perhaps the best piece of research on Russian sabotage to date. The dataset captures a broad sabotage toolset across physical and virtual domains: espionage, subversion, ransomware and supply-chain abuse, alongside information operations using disinformation, propaganda, deepfakes and conspiracy narratives. On the ground, activity ranges from arson and vandalism to GPS jamming and undersea interference. Some cases worth highlighting are the suspected water-supply tampering near German bases, attacks on telecoms towers along Sweden’s E22 corridor, the DHL parcel-bomb tests reported across Germany, Poland and the UK, and anchor-dragging by vessels that severed cables such as Estlink-2 and C-Lion1. Costs of repairs can run to tens of millions of euros, not accounting for economic disruption and policing burdens – or the morale effect on the populace.

Figure 2. Methods of Russian hybrid-warfare activity across Europe between Jan 2018 & June 2025 (IISS 2025).

The report also finds that exposure is amplified by structural weaknesses throughout Europe. Europe’s electricity grids average about 40 years in age, with roughly 60% of required EU investment needed just to modernise distribution networks – vital for military supply chains. Rail remains a single-point-of-failure risk for NATO logistics; cases in Poland showed local networks being monitored with track-side cameras. Dependence on the private sector is also a weak point. Around 90% of NATO military transport uses civilian assets, more than half of defence satellite communications are commercial, and three quarters of host-nation support is delivered by local firms. Undersea cables carry about 95% of global data and underpin an estimated 10 trillion US dollars in daily financial transactions, while over 70% of cable incidents annually arise from commercial marine activity, compounding the risk profile.

From Disruption to War: The Semantics of Sabotage

Semantics are critical in geopolitics. Elections, infrastructure, the economy, territory – all things critical to a sovereign nation, are all being attacked in Europe by Russia. In any war game scenario, attacks to these fundamental attributes to democracy would be assessed as hybrid warfare at the very least.

Russian surveillance drones have conducted frequent reconnaissance flights over eastern Germany to monitor Western arms deliveries to Ukraine, with Western intelligence services recording more than 530 sightings in the first three months of this year. Their purpose is to track shifting military transport routes in order to determine which weapons are bound for Ukraine and when new equipment or ammunition will arrive. German authorities have struggled to counter these espionage activities, as responsibility for security is divided: the Bundeswehr protects its own installations, while the Ministry of the Interior and civilian operators are responsible for infrastructure such as railways and LNG terminals.

At the same time, a suspected Russian GPS interference attack forced European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s aircraft to land in Bulgaria using paper maps after its navigation systems were disabled. Although no jamming signals were detected at the airport, Bulgaria reported that the aircraft could have picked up interference either from jamming signals or from other aircraft. The fact that Russia was immediately suspected, and the fear it provoked across Europe, speaks volumes about the escalating tensions that now extend well beyond Ukraine.

Poland has faced similar challenges. In fact, it is highly likely that these drone forays into Germany and Poland are for surveillance purposes as a prerequisite for future sabotage attempts. In early September, Poland tolerated the presence of Russian drones in its airspace without reprisals. Yet, in the early hours of 10 September, Poland - for the first time since the invasion of Ukraine - announced that, with the assistance of Dutch F-35s and other European allies, it had shot down multiple drones over its territory. The decision, it explained, reflected the sharp increase in drone incursions, which had already forced the closure of four Polish airports.

In response, Ukraine’s Deputy Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha warned:

“A weak response now will provoke Russia even more, and then Russian missiles and drones will fly even further into Europe.”

This assessment is persuasive. Russia continues to test the limits, confident that Europe remains vulnerable and fearful of escalation. Germany’s refusal to supply cruise missiles, despite the deployment of Storm Shadows and Ukraine’s development of the Flamingo cruise missile, underscores this hesitation. The parallel with 1939 is uncomfortable: a European strategy of denial and wishful thinking risks repeating the same mistakes. Poland, by contrast, seems less willing to accept the ‘grey zone’ framing that has paralysed European responses for three years.

Europe at a Crossroads

Russia has long understood the power of language in shaping Europe’s response. By operating in the margins of attribution and deniability, Moscow exploits the very ambiguity captured in the term grey zone. European leaders, in turn, have leaned on that terminology to postpone hard decisions, treating semantics as a substitute for strategy.

But words will not deter sabotage, drone incursions, or election interference. Nor will they prevent Moscow from pushing further so long as Europe signals it is more afraid of escalation than of attack. Outrage expressed in parliaments and press conferences achieve little if the incidents themselves remain categorised as something less than warfare.

Europe must therefore confront the reality: these are not grey zone activities, but components of a deliberate hybrid campaign. Recognising that distinction is more than semantics - it is the first step towards building the unity and resolve required to defend European sovereignty. If Europe continues to hide behind the language of ambiguity, Russia will go on defining the conflict on its own terms. If, however, Europe calls these attacks what they are, it may yet begin to seize back the initiative and even deter future attacks.

Europe is at a crossroads: continue retreating into the safety of semantics, or accept that the grey zone is over, hybrid warfare is here, and Europe must respond accordingly.

References

BBC News (2025) Poland says it shot down Russian drones after airspace violation. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c147065pzdzo (Accessed: 10 September 2025).

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) Hybrid warfare. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/hybrid-warfare (Accessed: 10 September 2025).

The Economist (2025) Russian sabotage attacks surged across Europe in 2024. 22 July. Available at: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2025/07/22/russian-sabotage-attacks-surged-across-europe-in-2024 (Accessed: 6 September 2025).

Herre, B. (2022) The world has recently become less democratic. Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/less-democratic (Accessed: 8 September 2025).

Insikt Group (2025) Russian influence assets converge on Moldovan elections. 3 September. Recorded Future. Available at:

https://www.recordedfuture.com/

(Accessed: 8 September 2025).

Institute for the Study of War (2025) Russia continues efforts to regain influence over Moldova. 5 September. Available at: https://www.understandingwar.org/research/russia-ukraine/russia-continues-efforts-to-regain-influence-over-moldova/ (Accessed: 8 September 2025).

Urbanic, J. (2025) ‘Russian spy drones over Germany: Why the Bundeswehr cannot shoot them down’, Euronews, 5 September. Available at: https://www.euronews.com/2025/09/05/russian-spy-drones-over-germany-why-bundeswehr-can-not-shoot-them-down (Accessed: 7 September 2025).

U.S. Department of Justice (2019) Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election. Volume I of II. Submitted by Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice.

Walker, S. (2025) ‘These people are disposable’: how Russia is using online recruits for a campaign of sabotage in Europe. The Guardian, 4 May. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2025/may/04/these-people-are-disposable-how-russia-is-using-online-recruits-for-a-campaign-of-sabotage-in-europe (Accessed: 6 September 2025).